Baseball Toaster was unplugged on February 4, 2009.

By Bruce Markusen

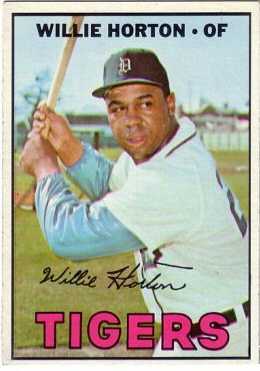

Willie Horton was a favorite player of mine, despite the fact that he never played for two of “my” teams (the Yankees or the Pittsburgh Pirates). One of the most popular Detroit Tigers of the sixties and seventies, Horton made news three years ago when the

Horton’s community activism stretches all the way back to his playing days—specifically to 1967. That season, Horton achieved legitimate hero status when he left Tiger Stadium immediately after a game and traversed directly into the streets of

Horton’s bravery under fire in 1967 probably didn’t surprise too many of his Tiger teammates, who had come to respect the quiet, rock-solid left fielder for his understated leadership abilities and unwavering professional approach to his work. Horton was one of just a few black players on the Tigers of ’67 and ’68 (along with backup outfielders Gates Brown and Lenny Green, starting pitcher Earl Wilson, and relievers Les Cain and John Wyatt) and the team’s only full-fledged African-American star. His status as the team’s most prominent minority made him extremely popular with black fans throughout

On the field, Horton’s presence loomed just as large as his civic and social involvement. He was one of the most feared hitters of his era, in part because of a sturdy five-foot, 11-inch, 225-pound frame of compact muscle, achieved at a time when few players lifted weights and perhaps none used steroids or other performance-enhancing, bodybuilding supplements. Pound for pound, no one appeared stronger than the robust Horton, whose thick wrists and forearms made him a Bunyanesque figure. A seven-time All-Star during his career, Horton typically hit 25 to 35 home runs a year and put up slugging percentages bordering the .500 neighborhood in an era when pitchers enjoyed most of the “enhancements” that the game provided (an expanding strike zone along with the ingression of larger, full-figured stadiums in Anaheim, Oakland, and Kansas City). Horton’s performance during the famed “Year of the Pitcher” in 1968 remains one of his landmarks; he hit 36 home runs and slugged .543 in a year where most hitters flailed away at far below their normal levels of production. He then hit .304 and scored six runs in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, but it was one of his fielding plays that really turned the Tiger tide during the Series. Never known as a particularly nimble fielder, Horton aggressively charged a ground single to left and then air-launched a one-hop throw to catcher Bill Freehan, who tagged out Lou Brock to stymie a Cardinal rally in the fifth inning of Game Five. The Tigers went on to win the potential elimination game, then claimed the next two matchups to take the Series.

Horton remained the Tigers’ everyday left fielder until 1972, when injuries and a slumping bat restricted Horton to 108 games and led to a time-sharing arrangement with the lefty-swinging Gates Brown. Tigers manager Billy Martin lost so much confidence in Horton that he began to play a catcher, the awkward and immobile Duke Sims, in the outfield during the American League Championship Series, squeezing Willie out of starts in the fourth and fifth games. (Horton, by the way, says that Martin’s insistence on using Sims in the outfield during the playoffs cost the Tigers the pennant that year. Sims went only 1-for-6 in the final two games and committed an error in the decisive fifth game, which the Tigers lost to the A’s, 2-1. In the meantime, Horton appeared only as a pinch-hitter in those two games, delivering one hit in two at-bats. Man, when will managers realize that catchers in the outfield do not work, as seen in the failed examples of Sims, Manny Sanguillen, and Todd Hundley?)

Plagued by a series of injuries, Horton lost the left-field job completely within three years, as the organization decided to capitalize on the relatively new designated hitter rule, which had been put into place in 1973. Horton made a smooth transition to the DH role in 1975, but slumped considerably the following summer. He remained in the role until the early days of the 1977 season, when the over-the-hill Tigers decided to expedite a youth movement by trading Horton to the Texas Rangers for pitcher Steve Foucault, a hefty right-hander who had enjoyed a mixed bag of success but would last only two more seasons in the major leagues.

Legendary for his superstitions, Horton then bounced from team to team, enjoying varying levels of prosperity as a DH with the Rangers, Cleveland Indians, Oakland A’s, Toronto Blue Jays, and Seattle Mariners, while also earning the Comeback Player of the Year Award after his career had been given up for dead. His newfound status as a journeyman prompted a new superstition to be added to his repertoire of rituals, this one involving his equipment. According to the Horton legend, whenever he changed teams he allegedly refused a newly issued helmet from his acquiring team, instead painting the colors and logo of the new team onto his existing headwear. (For those who collected cards in the 1970s, Horton’s 1978 Topps card with the Texas Rangers provides an example of the alleged artwork on his helmet.) During an interview I did with Horton on MLB Radio, I asked Horton if this was true; he confirmed it during our chat while displaying the pride of a skilled painter. True to form, Horton still owns the battered helmet, which appropriately features the old logo and colors of the Mariners—his last major league team.

Bruce Markusen is the author of seven books, including A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley's Swingin' A's. His newest book, a revised edition of Tales From The Mets Dugout, is now available from Sports Publishing. Bruce is a resident of Cooperstown, NY.

Geez... great article. It sure is nice to have some other 'old farts' around here.

I remember Willie pretty well. He was scary at the plate, although I don't remember his last years of travel that well.

At bat, he was like a fire hydrant with strong arms. I thinks today's fans can't appreciate what 30+ HRs was back in those days. Bobby Murcer was our best Yankee slugger back then, and his 2 best HR years were 33 and 27, averaging about 20 per full season. So Willie was definitely a force.

It is a terrible shame for the Black community that there doesn't seem to be that many Black atheletes stepping up these days. His behavior had a tremendous impact on his community that is hard to measure. And in those days, while I'll guess Horton made decent money, it's nothing like the financial riches today's players enjoy.

Thanks for the memories.

I'm just kidding...

Everyone knows Dukakis didn't have a chance in that election

Terrific. Loved the helmet story. Always feared him when the Bengals came to town. Just wondering about Billy's rep as a racist. Clearly, he did not like Reggie.

One item I failed to include in the article. Horton has ties to the Yankees. He served as Billy Martin's "attitude coach" with the Yanks in the 1980s. I believe he was the first and only attitude coach in major league history.

Comment status: comments have been closed. Baseball Toaster is now out of business.